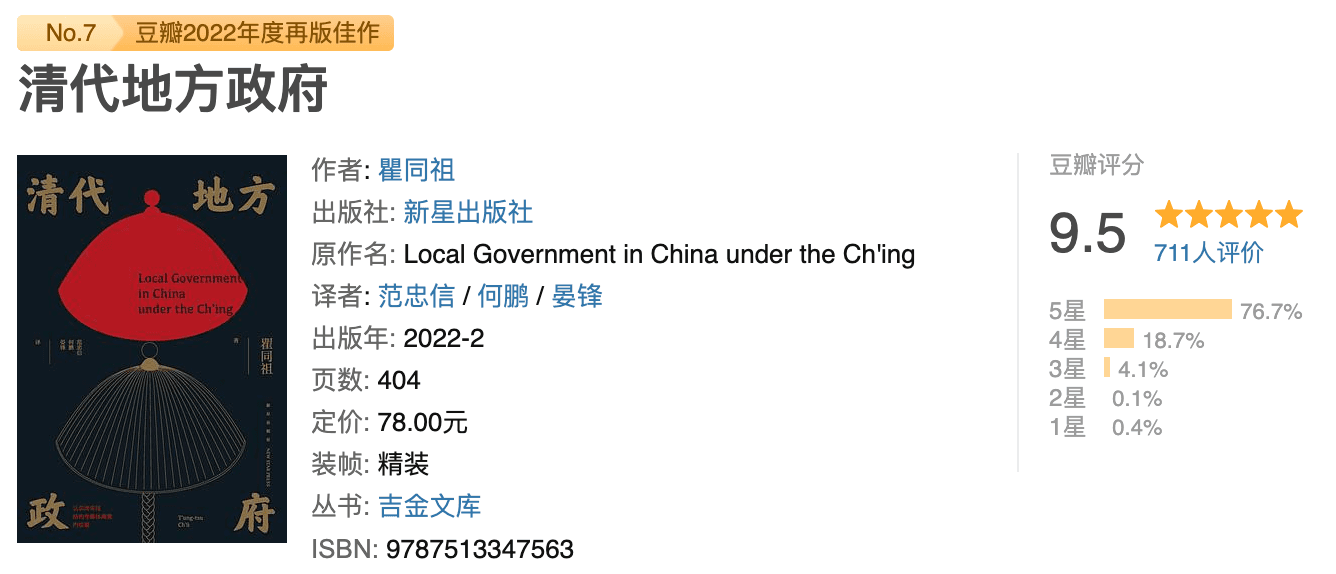

这是一本了解清代州县官如何管理地方的绝佳材料。结构清晰,内容明了,毫无废话。作者瞿同祖,其祖父瞿鸿禨,清末军机大臣。

之所以说其结构清晰,看目录就可知一二。先简单介绍州县政府,接着开始讲州县官,往下围绕州县官四大助手「书吏、衙役、长随、幕友」讲述他们的选拔及职责等方面,最后讲政府最重要的收入来源:税收,以及和当地行政息息相关的士绅阶级。

其中,关于州县官及四大助手的部分让我收获颇丰,或许是作者讲述的方式有层次及全面(通过选拔、任职、待遇、贪赃方式等方面),又或许是这些都是实实在在的个体,自己通过电视剧或者读书有些许了解但又不够深入,经过此书得以更全面地了解。

有几点值得记录下:

- 州县官的常俸不高:45-80 两 / 年,即使后来有了 500-2000 两 / 年的养廉银(培养廉洁的银子)也不够应付衙门日常开支。

- 州县官不能在家乡的省担任,面对陌生的环境,必须高度依赖当地的书吏,但又需要时刻提防狡猾的书吏贪渎 —— 毕竟书吏基本没有薪金。

- 四大助手中大部分人员都属于贱民,例如衙役中的捕快,长随。贱民不能参加科举,甚至会影响「三代」,严重怀疑现在的某些制度是沿用的清代制度……

- 幕友即师爷,地位较高,连州县官都得尊敬他们,不然人家随时辞职跑路。他们的待遇也是最高的,甚至收入高于州县官,毕竟州县官时常需要出钱应付上级或者满足其他开销。

从书中可知,地方官员或者工作人员的薪金基本是入不敷出的,因此,权力行使过程就会产生所谓的「陋规」,即丑陋的规矩。只要和人打交道,有流程,那就离不开陋规,千百种陋规甚至成为了书吏、衙役等人的主要收入来源,这也是为啥某些职位虽然是贱民,但仍然很多人争抢的缘故。

庙堂之人自然知道江湖之远的这些陋规,但他们也没办法,因为没有太多的钱去支付给这些基层官员,只能靠他们去想办法,能想到的办法自然就是压榨底层百姓 —— 只要不危及统治,庙堂之人自然是无所谓。因此,面对「无伤大雅」的行为,他们便睁一只眼闭一只眼。当然,到后期这些陋规发展得愈发猖狂,甚至被认为威胁到了帝国统治,皇帝才开始着手整治,比较出名且有效的便是火耗归公,这一政策的确有效减少了陋规。